At about 10:30 AM on March 14, as I was driving around town, I heard an announcer on TSN 1200 radio read a text from a listener. I can’t specifically say who the announcer was because I was driving my car and not paying full attention to the broadcast.

The listener was not fond of the trade the Senators had made to acquire Alex DeBrincat. He didn’t like it at the time of the trade, and he didn’t like it now. He trotted out the myth that the first year of every player who changes teams turns out to be a sub-standard season.

The host brushed off the part about not liking the trade, as people are entitled to their opinions. He largely agreed with the myth, softening it only slightly: “the first season of a player on a new team is usually a sub-standard season.”

This is exactly the sort of myth that can be checked with the two main rating systems used here at Stapled to the Bench: Productivity Rating (PR) and Value Rating (VR).

See the links below that explain PR and VR.

Analysis Notes

The first thing to do is to establish the players who will be used for this analysis. I will look at players who played three straight seasons for just one team and then played one full season with just one other team. Another qualification rule is that the player must be VR-Regular or better in his last season with his ‘first team’.

I will then compare the PR-Score of the player from his last year of his first team (Year 3) to the first year with his new team (Year 4). If the myth is true, more players will have a lower PR-Score in Year 4.

Calvin de Haan played for the Islanders in 2015, 2016 and 2017, then played for Carolina in 2018. He had played for the Islanders since 2011, but that doesn’t matter as we are only looking at the three years immediately before a change in teams.

In 2017 he was VR-First5, even though he played only 33 games that season. His Productivity Score (PR-Score) was 3.07: that placed him in the PR-Fringe category, entirely because he played only 33 games. In 2018 he played 74 games and had a PR-Score of 5.44 (PR-Regular), so he improved in his first year with his new team.

Calvin de Haan played one season in Carolina and moved to Chicago the following season. That move does not qualify for this analysis as de Haan was with Carolina for only one season prior to that change.

Players

There are 402 player-seasons where a player has played for the same team in the previous three seasons and are rated VR-Regular or better in the last of those three seasons and played for a single different team in the following season. 53 players qualified two times, and two players qualified three times. Some guys like moving, I guess.

Presenting Results

In the early stages of my analysis of this myth, I considered how the results should be presented. There were several different sized groups of players, so counts themselves could not be used.

I thought about using percentages, but percentages are best in black-and-white situations where there are only two options. 35% of the skaters in the NHL are defensemen: that’s a fine use for percentages.

And while, pedantically, every subsequent season would be either better than or worse than its preceding season, thus making percentages acceptable, some subsequent seasons are essentially the same as their preceding season. The results should recognize that players can have similar seasons, that there should be ties. For this study, seasons will be considered “similar” if their PR-Scores are within 0.2 of each other. It does not happen a lot.

Results will be presented in a win-loss-tie format. Having a better subsequent season will be considered a win, while having a worse subsequent season will be considered a loss and having equivalent seasons will be considered a tie. Since different-sized groups of players will be used, I will convert everything to an 82-game equivalent season record.

For example, there are 297 players who rated as PR-Regular or better in both 2020-21 and 2021-22. By raw counts, 133 players had a better 2021-22 season, 128 had a better 2020-21 season and 36 had similar seasons.

The raw record of those players would be 133-128-36 while the 82-game season equivalent record would be 37-35-10.

Results 1

Of the 402 qualifying players, 227 declined in productivity score in their first year on a new team, with an average PR-Score drop of 0.29.

The season equivalent record of players moving to a new team is 32-43-7. Players who change teams usually do poorly in their first season on a new team.

It looks like the myth is confirmed. Are we finished? Not quite.

Results 2

In considering what else could cause a decline in PR-Score, I thought about the PR-Score itself. Players that have a good (for them) season don’t usually follow that up with another good season.

My definition for a player having a good season was that his PR-Score in his last season with the first team was higher than his VR-Score for that season.

In 2010 Max Talbot had played his fourth straight season for Pittsburgh: his VR-Score was 4.23 while his PR-Score was 5.05. He moved to Philadelphia in 2011 and improved his PR-Score to 6.58. (2011 was undoubtedly Talbot’s best season.)

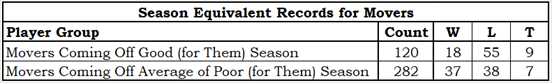

I found 120 players who were coming off a good year: 27 improved, 80 declined and 13 were about the same. Their average PR-Score dropped 0.99.

The season-equivalent record for these 120 players was 18-55-9. The other 282 players, those who were not coming off a good-for-them season, had a season-equivalent record of 37-38-7.

We’ve found a subset of moving players who are almost completely responsible in the drop amongst players who move. It still looks like the myth is confirmed, and the only problem is the wording of the myth could be more specific. Are we done and dusted? Not quite.

Results 3

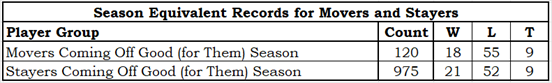

What else can be done? We can compare movers who had a good-for-them season with stayers who had a good-for-them season.

A stayer is a person who played three seasons for just one team and played their fourth season for just that same team. As more players stay than move, there are 975 players who played four consecutive years with just one team and whose third season was a good-for-them season.

When players have a good-for-them season they usually have a drop in performance the next season, and it is usually a significant drop.

These data destroy the myth. Players coming off a good season usually have a poor subsequent season, whether they move to a new team or stay with their old team.

Summary

A quick analysis (Results 1) confirmed that the group of players who move tend to have a drop in productivity in their first season with their new team. A deeper look at the data (Results 2) showed that the drop was almost completely due to moving players who were coming off a good season.

The comparison of movers to stayers (Results 3) destroyed the myth. Players coming off good seasons tend to have a drop in their subsequent seasons, whether they stay (21-52-9) or move (18-55-9). Their decline is very similar in its depth.

Myth busted.

How did this myth begin? My guess is that fans had great anticipation of how good some players would be on their team in their first season, after having had a good season with the players’ previous teams. These fans usually were disappointed, and assigned blame for the players drop in productivity to their having moved, rather than to it being the natural result of the player coming down from a good season.

As a group, fans tend to focus on “the good players who move”. On average, there are eight players a season who move after having a good season. There is no focus on “all the players who move”. Twenty more players, on average, move after having below-average or average seasons. Anyone who wants to say that the myth is confirmed because the group of players coming off non-good-for-them seasons had a losing record (37-38-7) doesn’t understand the meaning of the word “usually.” If you flipped a coin 75 times and had 37 heads and 38 tails, the coin doesn’t “usually” land on tails.

Alex DeBrincat scored 40 goals in Chicago last season, and many Ottawa fans expected him to score 40 this season, if not 50 (or 60). That he’ll score less than 30 goal is a disappointment for the fan base and is also a drop in his productivity. That drop isn’t a result of his moving; it is a result of his coming off a good season.

Reference Articles