When I started this article, it was quite early in the season, and it looked like Thomas Chabot had inherited the target that used to lay on Cody Ceci’s shoulders. Chabot is a very good defenseman, but he is not playing like Bobby Orr, and he is certainly not playing as well as we think he can, so therefore he is a bad defenseman. Uneasy lies the helmeted head that fans are focused on.

The most frequent complaint I have heard on the local radio (TSN 1200) is that Chabot isn’t making his teammates better. A host said something like: “Chabot has to play better, and he has to make his defensive partners play better.” I am going from memory because I was listening to the radio while driving around doing my grocery shopping. I wonder, do radio stations provide transcripts of their shows? I would love to use a quote.

While first part of the statement is impervious to analysis (see the summary), statistics can be used to investigate the second part. Does [any player] make his teammates better? Set [any player] to [Thomas Chabot] and solve the equation.

The only things we need are a definition of “play better” and an appropriate equation.

Better Play

I play pick-up hockey with a bunch of mostly retired gentlemen. The range of skill of the players is significant: there are a few guys who play extremely well, a larger group that plays at a good level, and then there’s me.

I do n0t “play better” when the excellent players are on the ice because I can’t “play better.” But when the better players for my team are on the ice with me, play is easier for me. If I move myself to an open position, they will pass to me. If they take a shot and I’m near the net, there can be a rebound opportunity. If the other team has the puck, the better players don’t let them get off good shots, and frequently take the puck away from them.

We don’t keep statistics, but if we did, my Corsi (shot attempts) would be way better when playing with the excellent players than when I am on the ice without them.

Corsi: An Appropriate Statistic to Measure “Better Play”

Corsi reflects the game flow in hockey. If your team has more shot attempts than your opponents, your team’s Corsi is positive. Corsi is also measured at the player level, reflecting how well the team played when the player was on the ice.

The variation of Corsi that will be used in this article is Corsi per 60 minutes of 5v5 play (C/60). If a player was on the ice for 30 minutes of 5v5 play, and his team had 24 shot attempts and gave up 21, the player’s C/60 would be +6.00: ( 24-21 ) * ( 60/30 ).

We Interrupt this Article for a Brief Message from your Sponsor

The biggest issue with writing an article about the season during the season is that the season keeps changing. When work on this article began, the Senators had played ten games. While discovering how best to present the findings and working on the wording, Ottawa played three more games. Data collection was frozen at that point, as another game or two of statistics wouldn’t make things any clearer, and constantly updating the data was making the writing process even longer.

We now return you to the article.

Does Chabot make other Players Play Better?

Using Corsi as the measuring stick, question I can answer is “Do players have a better Corsi when they play with Chabot than when they play without Chabot?”

First, I gathered the Corsi data for Ottawa players from the current season. Erik Brannstrom, for example, had 163 minutes of 5v5 play during which Ottawa took 179 shot attempts and conceded 147 shot attempts. His C/60 was +11.78.

The next step was to get the data of these players when they were with Chabot (on NaturalStatTrick, this is done using the Teammates report). Brannstrom was on the ice with Chabot for 60 minutes, where Ottawa had 73 shot attempts and gave up 57. His C/60 playing with Chabot was +16.01. (He was a few seconds shy of 60.00 minutes.)

Step three was determining each player’s C/60 when playing without Chabot. Brannstrom’s C/60 without Chabot was +9.31. Brannstrom played better when Chabot was on the ice: his C/60 was +6.70 better (+16.01 with Chabot compared to +9.31 without Chabot).

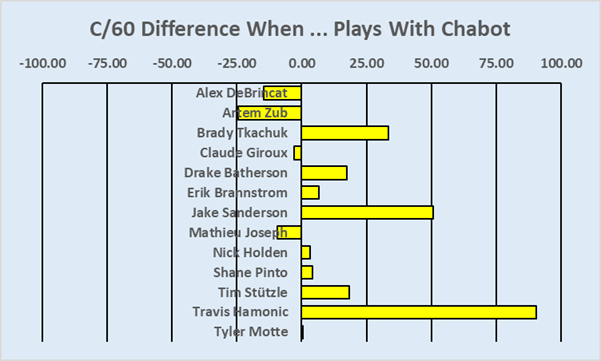

The chart below shows the data for each player on Ottawa who had at least 117.0 minutes (9.0 minutes per game for 13 scheduled games) of 5v5 ice time in the first 13 games of 2022. If a player’s bar extends to the right, he played better when Chabot was on the ice.

Travis Hamonic’s numbers show what can happen when you play with a really good player for a small amount of time. In 175 minutes without Chabot, his C/60 is -0.69. In 16.7 minutes with Chabot, his C/60 is a ridiculous +89.91.

Chabot and Zub

The player who has been most negatively impacted during his shared ice-time with Chabot in 2022 has been Artem Zub. When Zub was injured early in the 2022 season, Ottawa made several attempts to find a satisfactory partner for Chabot.

Zaitsev was one candidate, presumably because his last name started with a “Z.” I discovered a little later in my research that the most frequent partner for Chabot from 2019 through 2021 was actually Zaitsev, so it’s not like they were strangers to each other. Several iterations of partners were determined to be failures as Ottawa went into a losing streak at the same time as they lost Zub (that is a coincidence, by the way).

The idea for pairing Zub and Chabot is that Zub is the yin to Chabot’s yang, the defensively responsible partner that lets Chabot do his offensive stuff with a degree of safety. Combining these opposite but interconnected forces is supposed to make Ottawa better. Unfortunately, the data show that putting them on the ice at the same time makes Ottawa worse than having them on the ice separately.

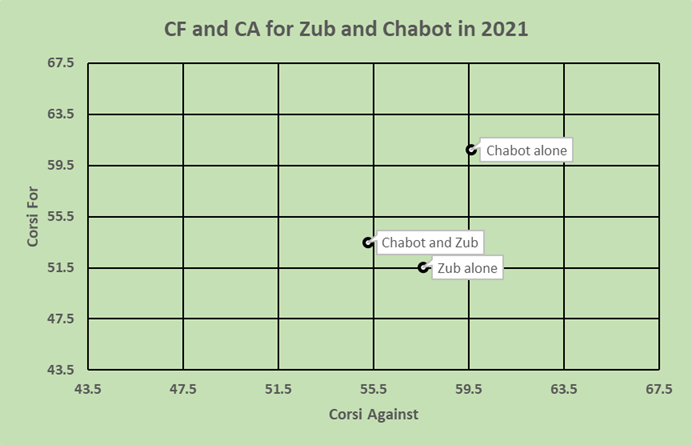

The following chart shows Corsi data for Zub and Chabot from 2021, where they played together for more than 1,000 minutes and the same problem occurred.

Ideally, you would want your dot to be in the top left side of the chart, where you have lots of Corsi For (CF) and little Corsi Against (CA). Playing without Zub, Chabot’s CF is 60.7 and his CA is 59.6, while playing with Zub his CF is 53.5 and his CA is 55.3. Zub’s presence with Chabot reduces Ottawa’s shot attempts against, at the cost of also reducing Ottawa’s shot attempts for.

The problem is that Ottawa is plus-Corsi when Chabot is on the ice without Zub, and minus-Corsi when he is playing with Zub. Ottawa lost 7.2 CF but only lost 4.3 CA. Using the Pythagorean formula for standing points, Ottawa was a 92-point team when Chabot was on the ice without Zub, but an 88-point team when Chabot and Zub were on the ice together.

Summary

I can’t believe that people would expect that any really good player would be able to bring any weaker player up to his level of play when they are on the ice together. Paul Coffey didn’t turn Lee Fogolin into a Paul-Coffey-clone when they played together.

The original statement that led to this article was that Chabot had to play better and he had to make other players play better.

I didn’t directly address the first part of that statement in this article, because the possibility that Chabot is not playing at his best is almost 100% true. The same statement, with the same degree of truth, could be used with any player in the league. Thomas Chabot has to play better. Connor McDavid has to play better. Auston Matthews has to play better. Austin Watson has to play better. It is the sort of statement your least favourite boss would make. (You need to write that PL/1 code better.)

This article deals with the provable portion of the original statement: does Chabot make the players he plays with better? The data shows that he absolutely does. His detractors will now probably say he could make them play even more better.

Summary, Part Two

Another focus of this article was the Chabot-Zub defensive pairing. In the Canadian Doubles article I recommended they play apart because Ottawa was really bad when both were not playing, better when either was playing, and even better when they were on the ice together. The underlying data for that article was different than used in this article: three seasons instead of one season, goals rather than Corsi.

Having negative Corsi data and positive goal data is unusual: it is like saying that the operation was a failure, but the patient lived. Being charitable, this could have happened because Ottawa had more dangerous shot attempts than their opponents did due to Zub’s defensive prowess.

I am not going to keep digging at this for three reasons: I am writing an article rather than a book; the article is long enough as it is; a little mystery in one’s life is a good thing.