While I was having a beer with a sports friend the conversation turned to hockey. He, a lifelong Maple Leaf fan, noted that Toronto had not had strong defensemen in a long while and that you can’t win playoff games without a strong defense.

He didn’t know I write hockey articles, and I didn’t enlighten him. I let him go on about the Leafs because he was 50% right: the Leafs haven’t had strong defensemen in a long while.

While he was venting I thought about ways I could show the strength of a team’s forwards and defensemen over time. The result, which you’ll see in this article, is a chart that looks like a hockey rink!

Historic Strengths – Terms Defined

For this article, history is the period from 2016-17 through 2023-24, and a team’s strength is their three best forwards and two best defensemen.

Identifying First-Line and First-Pair Players

Productivity Rating (PR-Score, specifically) was used to identify each team’s three best forwards and two best defensemen. PR-Score is a number based on the statistics generated by a player in a season, and it is in the range of zero to ten(-ish). The terms “first line” and “first pair” will be used to identify them, even though the identified players didn’t always play as a line or a pair.

A star player who missed many games in a season usually did not qualify as a top player for his team in that season. In 2022-23, John Carlson (WSH, D) did not qualify for the first pair for the Capitals as he missed more games than he played. Thomas Chabot (OTT, D) did not qualify for the Senators, as he missed 31 games.

Players who were traded mid-season were excluded from consideration, as this simplified my work and was accurate probably 99.73% of the time. A traded player essentially misses a significant number of games for both teams he plays for in a season and is extremely unlikely to qualify for first-pair or first-line for either team as a result.

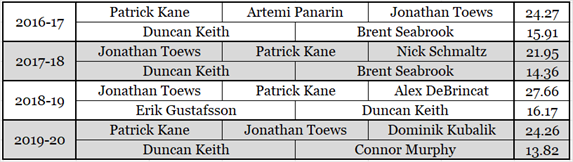

The total PR-Score of the players from each first pair and first line was calculated, and then the rank of those units was determined. For example, allow me to show you the results for the 2016-17 Chicago Blackhawks.

Way back when, the top two defensemen of the Chicago Blackhawks were Duncan Keith and Brent Seabrook, who had PR-Scores of 8.80 and 7.10 respectively. Their total PR-Score was 15.90, which made them the 14th-best first-pair in the league. The Blackhawks’ top three forwards were Patrick Kane (8.84), Artemi Panarin (7.98) and Jonathan Toews (7.45). Their total PR-score was 24.27, making them the 6th best first-line.

Now let’s take a look at the chart that will be used.

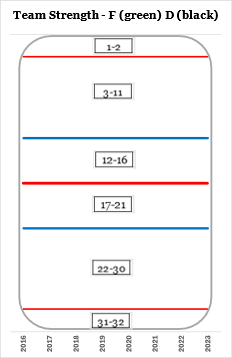

The Hockey Rink Chart

The background of the Hockey Rink Chart gives the impression of a hockey rink. You can see the boards (grey line around the body of the chart), goal lines (red lines at the top and bottom), blue lines and the centre red line.

The numbers in boxes show the ranks a team has to have to get a data point into that area, from one to two at the top of the chart (best teams) to 31 to 32 at the bottom of the chart (worst teams).

A team’s first-line strength across the seasons will be shown with a green line, while the first-pair strength will be shown with a black line.

The first-pair lines vary more from season to season than the first-line lines. Defensemen suffer injuries more frequently than do forwards, and the third-best defensemen are usually further from the top two defensemen than the fourth-best forward is from the top three forwards.

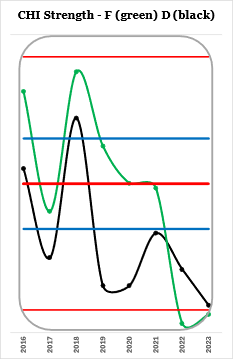

Let us now return to the Chicago Blackhawks and see their strength chart.

Chicago – Strengths, 2016-17 to 2023-24

The Chicago Blackhawks’ first line ranked 6th best in 2016-17, so their data point is between the top goal line and the top blue line. Their first pair was slightly above mid-point at 14th, so that data point is above the center red line.

In general, Chicago has been in a state of decline since the 2016-17 season, and that is reflected in their Strengths chart. Last season their first pair (Seth Jones, Alex Vlasic) ranked 30th in the league and their first line (Jason Dickinson, Connor Bedard and Nick Foligno) ranked 31st.

The fate of a team and the strengths of their first line and first pair are largely, but not completely, intertwined. Chicago’s chart is about what we should expect.

What might not have been expected is how bouncy the lines are. Let’s take a look at Chicago’s first lines and first pairs for the first four seasons of the chart.

At forward (the top line in each season’s pair of rows), Toews and Kane were consistent members. When there was a good third forward (Panarin in 2016-17, DeBrincat in 2018-19) the first line scored higher and ranked better.

At defence, Duncan Keith was a consistent member, even though his productivity was starting to decline. Brent Seabrook’s career was also declining, and his decline was sharper. With no disrespect intended towards Connor Murphy, a good season from Connor Murphy is not the same as a good season from Brent Seabrook.

Why did Chicago’s strength decline? Chicago had two great defensemen, and they aged. In Toews they had one of the best centers in the league, and he aged. Patrick Kane got older, but he didn’t age: his play didn’t decline. Overall, they lost productivity from three exceptional skaters and the replacements didn’t measure up. “Next man up” my arse.

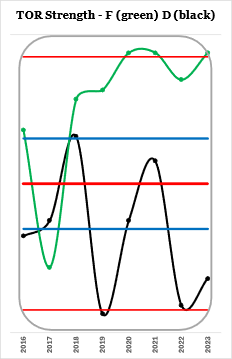

Toronto – Strengths, 2016-17 to 2023-24

A rapid look at Toronto’s Strength chart shows my sports friend was right: Toronto has had a good first line (green line) and average-to-poor first pair (black line).

2017-18 can be explained by Auston Matthews having missed 20 games while Marner and Nylander scored 22 and 20 goals. Twenty-goal seasons are nice, but they aren’t special. 60 forwards scored between 20 and 25 goals in 2017-18, another 58 scored more than 25 goals. That’s four 20+ goal scorers per team, on average.

The 2018-19 improvement came about thanks to a surge in performance by Mitchell Marner and the acquisition of John Tavares. Since then Toronto has been blessed with two marvelous forwards (Marner, Matthews) who have been healthy and productive.

As for the defensemen, well, they are like the less talented siblings in a large family. They have some skills, but they aren’t at the Matthews-Marner level. Two seasons (2019-20, 2022-23) in particular could be described as “woefully inadequate.”

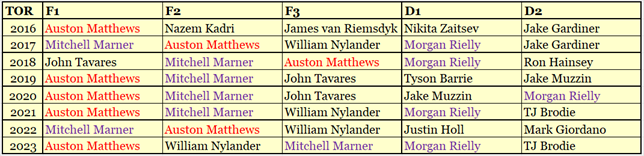

Morgan Rielly has been Toronto’s main defenseman since 2016-17. He is a good defenseman (PR-First5 to PR-Star when not injured) who has had several injury-impacted seasons. His three best seasons correspond to the three upticks in Toronto’s black line: 2018, 2021, 2023. The following table shows which players qualified as Toronto’s first line or first pair in the period being evaluated.

Selected Torontonians

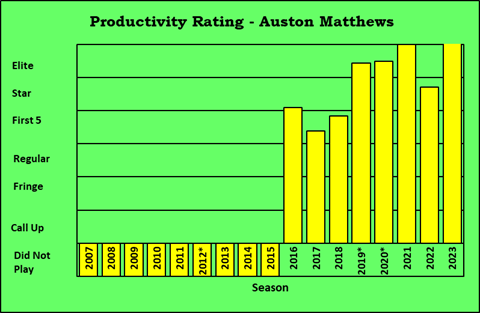

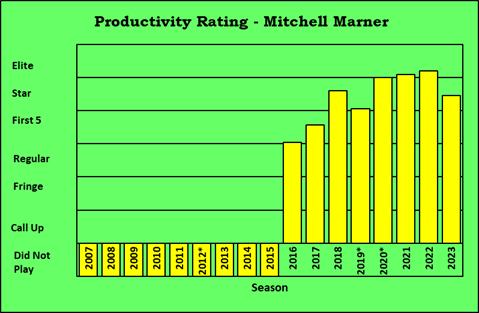

Here are the Career Productivity charts for Auston Matthews and Mitchell Marner.

Is there a team in the league that would not instantly trade their top two forwards even-up for Matthews and Marner? Edmonton wouldn’t (McDavid and Draisaitl). Colorado wouldn’t (MacKinnon and Rantanen). Most other teams would make the trade in a heartbeat.

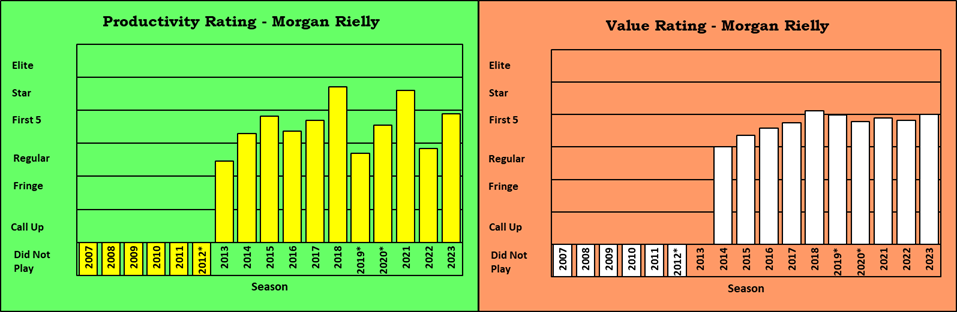

Next will be the Productivity Rating and Value Rating charts for Morgan Rielly.

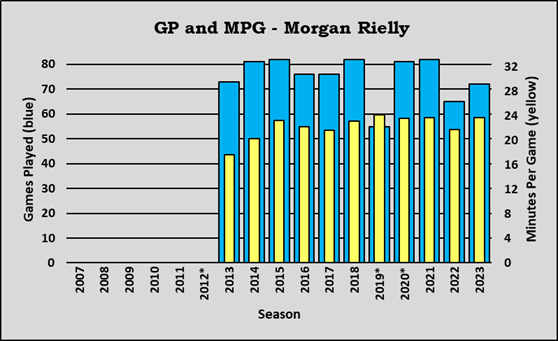

Rielly’s Productivity Rating chart (left) shows the impact that injuries can produce in a defenseman’s career. Let me show you a rarely shown third chart for a player, his GP and MPG chart (games played and minutes per game).

he thick blue bars show the number of games played, while the thin yellow bars show minutes played per game.

Rielly’s low PR-Score in 2019-20 is related to having missed games (which will happen when you have a fractured foot). While I cannot prove it, I believe his 2020-21 and 2021-22 PR-Scores show that his foot injury was still affecting his play in 2020-21. He played about the same amount in both seasons, in terms of average ice time and percentage of schedule played but was a PR-Category better in 2021-22. His PR-Score in 2022-23 looks lower than it should be, even though he missed 17 games with an MCL sprain. The MCL Sprain came in the early part of the season, and it is easy to guess that this injury affected his play on his return.

His Value Rating chart shows his value, which is an estimate of what his PR-Score would be if he played most of the games in a season. Value-wise, Rielly is at the top of the First5 category. League-wise, that makes him somewhere between the 30th and 40th most valuable defenseman. Article-wise, this reinforces the main point, which is that Toronto has an extremely good first line and a pedestrian-at-best first pair.

So, Toronto has had a weak top pair with respect to the league. What could they have done to improve their defensive corps?

Improvement Through the Draft

If you are looking for a top-pair defenseman in the draft, you need a high first-round pick. While there are top defensemen who were not selected in the first round of the draft, those players are exceptions.

Being blessed with excellent regular season results Toronto has been saddled with late first-round draft picks, minimizing their chances of finding a great defenseman. What have the Leafs done with their first-round draft picks since 2016-17?

2016 #1 overall: used on Auston Matthews, a forward. You might have heard about him.

2017 #17 overall: defenseman Timothy Liljegren, who started playing regularly in 2021 and has been at the bottom of the PR-Regular category since then.

2018 #29 overall: defenseman Rasmus Sandin, who was slightly better than Liljegren but who was traded to Washington in 2022-23 for Erik Gustafsson. Gustafsson had a similar Player Rating to Sandin (middle PR-Regular) but had the huge disadvantage of being eight years older (31 to 23). Between Sandin and Gustafsson, only Sandin had a long-term future. Based on the at-the-time talent and future potential of the players in the trade, it is baffling why Toronto traded Sandin’s future away in return for what turned out to be nine regular season games from Gustafsson.

2019: no first-round pick. It was part of a package sent to Los Angeles in return for defenseman Jake Muzzin. Muzzin was a PR-First5 defenseman when he was acquired but he was at the age where players started to decline and he did. His best season in Toronto came in the pandemic-shortened 2020-21 season, where he was at the top of the PR-First5 category. Due to injuries, he dropped to PR-Fringe, then to PR-CallUp, and then to PR-ProfessionalScout (not an actual PR category).

2020 #15 overall: forward Rodion Amirov.

2021: no first-round pick. It was used in the acquisition of forward Stefan Noesen. No, really, I’m not making this up. The Leafs traded a first-round pick for a forward who was, at the time of the trade, solidly in the PR-Fringe category. He played one regular season game for the Leafs. In his late-career surge in Carolina, Noesen has moved up to the bottom of the PR-Regular category.

2022: no first-round pick. The Leafs sent Petr Mrazek (G) and their #25 pick to Chicago in return for a second-round pick, where they selected forward Fraser Minten. The trade smacks of being a salary dump. Chicago accepted Mrazek’s contract in return for a better draft pick.

2023 #28 overall: forward Easton Cowan.

2024 #31 overall: defenseman used on Noah Chadwick, who is probably years away from playing in the NHL.

Acquire Talent Through Trades

The problem with trading is that to get a player of value you have to give up a player of value. Nobody is going to trade away a first-pair defenseman for a bucket of pucks and a leaking Zamboni. For Toronto to get a first-pair defenseman, they’d almost certainly have to give up one of their first-line forwards.

Toronto has acquired a couple of defensemen through trades since 2016-17 (Gustafsson and Muzzin were mentioned in the previous section). Gustafsson was either in decline or almost certain to be going into decline when acquired, and he wasn’t a first-pair defenseman in his peak seasons. Muzzin was a first-pair defenseman when he was acquired, and he was their best defenseman in 2020-21. Then concussions and a spinal injury brought him down.

Improve From Within

This idea is related to the “next man up” syndrome, where an injury to a good player requires a shift in the workload and responsibilities of other players. Lesser players are expected to play better because the team needs them to replace the skill level of the injured players.

Does it take any more than two seconds of thought to realize how dumb this expectation is?

The reason that a player is a lesser player is that he doesn’t have the skills of a better player. If a lesser player could play at a higher level, he would already be doing so. The reason that Max Domi doesn’t score 25 goals a season is that he isn’t capable of doing that.

Instead of the “next man up” syndrome, “improving from within” is a “this specific man up” syndrome. Only a couple of seconds of thought are needed to determine whether the idea is a fantasy.

No amount of coaching will take a player above the innate skill level he has. If coaching could improve a player, why haven’t the coaches in Toronto brought Morgan Rielly to the Adam Fox level of play? Why would a coaching staff only improve one player? Why have only one Morgan Rielly (or Adam Fox) when you could “coach up” six of them?

Summary

A related article to this one, called Historic Team Depth of Talent, will look at the depth of talent on a team, where “Depth” is all players except the first line and first pair.

Related Articles